Saving Lives Through the Science of Suicide Prevention

.

National Institute of Mental Health

If you asked people about the most common causes of death in the United States, they’d likely mention conditions like heart disease, stroke, or diabetes. And they’d be right. But there’s another leading cause that often goes unmentioned: suicide. This stark reality is reflected in the data: In 2020, suicide was among the top four causes of death among people ages 10 to 44, and the 12th leading cause of death overall in the United States.

The issue has never been more urgent.

“No one should die by suicide,” said Joshua A. Gordon, M.D., Ph.D., Director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). “We can’t afford to wait—which is why NIMH is investing in research to identify practical, hands-on tools and approaches that can help us prevent suicide now.”

NIMH has made suicide prevention a priority, spurring large-scale research efforts to improve screening, risk assessment, and intervention. As a result, evidence-based strategies are now being implemented in health care settings across the country as a core component of the suicide prevention toolkit.

Addressing urgent needs

In the spring of 2006, Lisa Horowitz, Ph.D., M.P.H., visited NIH to interview for a position on the psychiatry consult service at the NIH Clinical Center. Just a few months earlier, a patient receiving inpatient medical care at the Clinical Center had died by suicide .

“When I came to apply for the job, the whole building was still reverberating around this suicide,” recalled Horowitz, who is now a senior research associate in the NIMH Intramural Research Program.

As a research fellow at Boston Children’s Hospital, Horowitz developed a triage tool that nurses could use in the emergency department to screen pediatric mental health patients for suicide risk. Her interview with NIMH Clinical Director Maryland Pao, M.D., planted the seed for what would turn into an entire line of research at NIMH.

“We were having lunch at the conference table in her office, and Dr. Pao asked, ‘Do you think we could use your screening tool for all patients, not just mental health patients?’”

To find out, Horowitz and Pao collaborated with researchers at several pediatric hospitals to launch a multisite study in pediatric emergency departments. Their aim was to develop a suicide risk screening tool that would allow clinicians to quickly identify which patients need further assessment.

Results from the study, published in 2012 , showed that a “yes” response to any one of four screening questions identified 97% of young people who met the criteria for “clinically significant” risk on a standard 30-item suicide risk questionnaire. Notably, the screener—now known as the Ask Suicide- Screening Questions tool, or ASQ—only took about 20 seconds to administer.

Although other suicide risk screening tools existed at the time, the ASQ added a brief, easy-to-use option to the screening toolkit.

Since the original study, the ASQ has been validated in other medical settings, including inpatient medical-surgical units and outpatient specialty care and primary care clinics. It has been validated for use with adults, as well.

Casting a wide net

On the surface, asking every patient who receives care in a medical setting to complete a suicide risk screening may seem unnecessary or excessive. But research shows that this approach, known as universal screening, identifies many people at risk who would otherwise be missed.

“What we’ve learned is that people who come to the emergency department with a physical complaint may also be at risk of suicide, but they might not reveal that unless you ask them directly,” said Jane Pearson, Ph.D., Special Advisor on Suicide Research to the NIMH Director.

With universal screening tools, clinicians don’t have to discern which patients are at risk.

“It’s not realistic to expect health care providers to be able to figure out who they should screen and who they shouldn’t,” said Stephen O’Connor, Ph.D., Chief of the NIMH Suicide Prevention Research Program. “When screening is universal, it becomes standardized, and it sets the expectation that every patient will be screened.”

This is critical because health care providers are in a unique position to identify people at risk—indeed, data show that more than half of people who die by suicide saw a health care provider in the month before their death. Research also shows that screening results can predict later suicidal behavior, which means screening tools present an opportunity to intervene early.

As part of NIMH’s commitment to prioritizing suicide prevention research, the institute supports innovative extramural projects focused on universal suicide risk screening. Among these projects is the Emergency Department Screening for Teens at Risk for Suicide (ED-STARS) study, launched in 2014.

In collaboration with the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network, ED-STARS researchers analyzed youth screening data from 13 emergency departments to develop the Computerized Adaptive Screen for Suicidal Youth (CASSY). They designed CASSY to adjust the screening questions based on patients’ previous responses to assess their overall level of suicide risk.

The researchers then tested whether CASSY predicted real-world behavior in a separate sample of more than 2,700 youth. The results showed that CASSY accurately identified more than 80% of youth who went on to attempt suicide in the 3 months after the screening.

Integrating interventions

While evidence clearly shows that universal screening can aid suicide prevention efforts, it also shows that screening is just the beginning.

“Screening is one part of the story,” said O’Connor. “When people screen positive for suicide risk, it’s important to follow that with a full assessment and evidence-based approaches for intervention and follow-up care.”

Key findings come from the NIMH-supported Emergency Department Safety Assessment and Follow-Up Evaluation (ED-SAFE) study. Designed as a multi-phase clinical trial, the ED-SAFE study allowed researchers to assess the impacts of universal suicide risk screening and follow-up interventions in eight emergency departments over 5 years.

In the first phase, adult patients seeking care at a participating emergency department received treatment as usual. The second phase introduced universal suicide risk screening—all emergency department patients completed a brief screening tool called the Patient Safety Screener.

The third phrase added a three-part intervention. Patients who screened positive on the Patient Safety Screener completed a secondary suicide risk screening, developed a personalized safety plan, and received a series of supportive phone calls in the following months.

As a result of universal screening, the screening rate rose from about 3% to 84%, and the detection rate of patients at risk for suicide rose from about 3% to almost 6%.

Importantly, findings from the third phase showed that it was screening combined with the multi-part intervention that actually reduced patients’ suicide risk. Patients who received the intervention had 30% fewer suicide attempts than those who received only screening or treatment as usual.

Laying out a roadmap

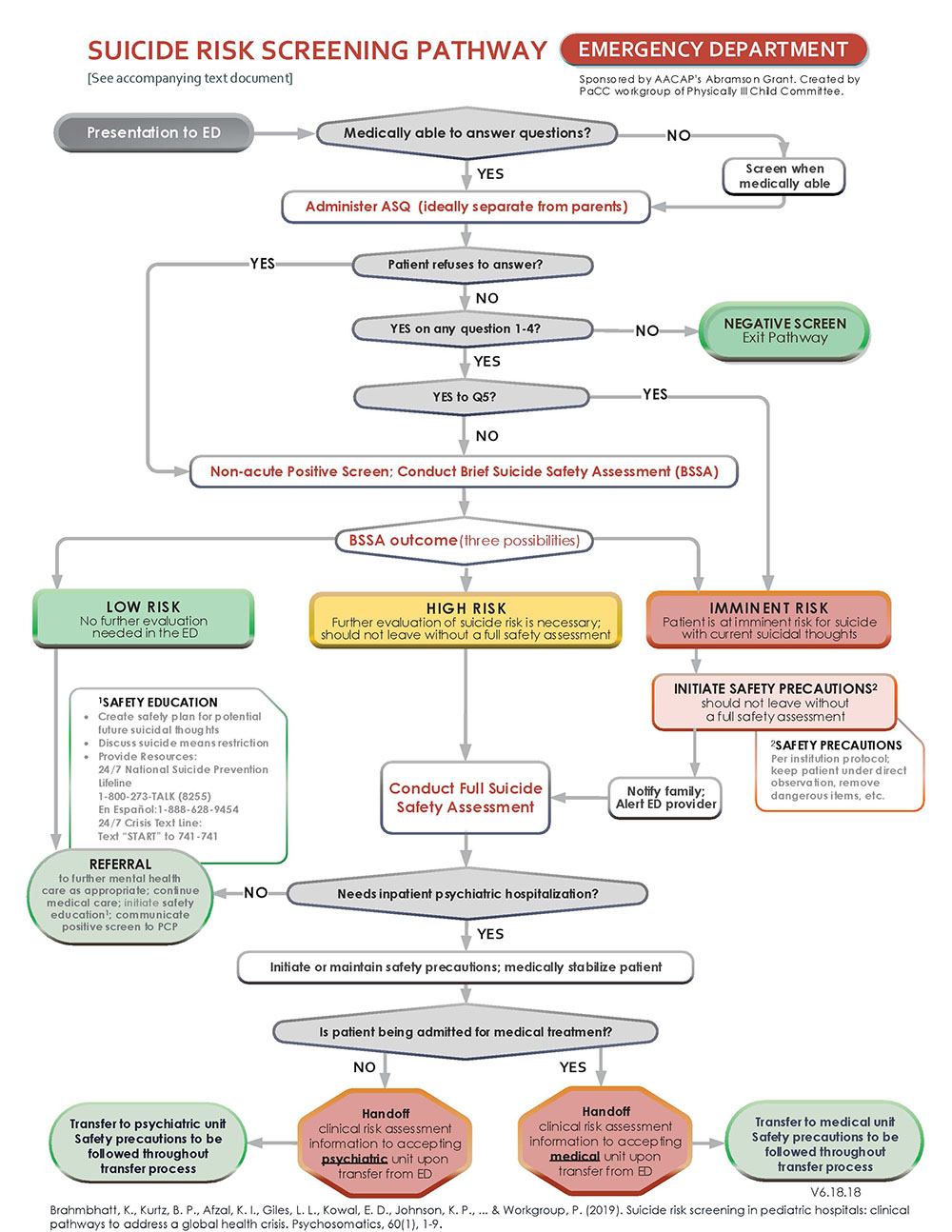

Ensuring that health care providers have a clearly delineated clinical pathway that links universal screening to the appropriate next steps can help them accurately assess and address their patients’ needs.

Patients may worry that they’ll automatically be hospitalized if they tell their health care provider that they’ve had suicidal thoughts in the past. But the reality is that only a small proportion of patients who screen positive on the initial screen will need urgent inpatient care—the majority are more likely to benefit from outpatient follow-up and other types of mental health care.

“With a clinical pathway, clinicians can have a conversation with their patients and give them an idea of what to expect,” said Pearson. “Screening has to be part of a workflow that accounts for different levels of risk, and you have to put all those pieces together.”

To health care providers already under considerable strain, rolling out universal suicide risk screening may seem like a tall order. But NIMH-supported research shows that it can work across a range of settings, from small specialty clinics to large health care systems.

Building on this work, Horowitz and colleagues in the NIMH Intramural Research Program have developed an ASQ toolkit that includes clinical pathways, scripts, and other resources tailored to the medical setting and patient age. These evidence-based clinical pathways, in turn, provided a scientific basis for the Blueprint for Youth Suicide Prevention developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

“The biggest thing I’ve learned is it has to be flexible,” noted Horowitz. “You’re not going to have the same access to care in rural Alaska that you’d have in New York City, so it’s important to help clinicians figure out how to adapt a pathway for their setting or practice.”

For example, large health care systems may be able to adopt certain technologies, such as computer algorithms, that can integrate electronic health record data into the screening and identification process. NIMH-supported research is exploring this data-based approach to risk identification in Veterans Health Administration hospitals, managed health care systems , and other large-scale settings .

However, other medical settings—including many primary and specialty care clinics—may prefer lower-resource approaches that are easy to adapt, such as brief, self-report screening tools.

“Having options is important for implementation. It depends on how health systems can leverage resources and incorporate them into the workflow,” said Pearson. “That’s why NIMH is investing in research on multiple, complementary approaches.”

Putting science into practice

To accelerate research that can make a difference in the near term, NIMH has launched a Practice-Based Suicide Prevention Research Centers program. The program aims to support clinical practice settings as real-world laboratories where multidisciplinary research teams can develop, test, and refine suicide prevention practices at each step of the clinical pathway. The centers are engaging with service users, families, health care providers, and administrators to ensure services are relevant, practicable, and rapidly integrated into the clinical workflow.

“The intent is that these practice-based centers will serve as national resources,” explained Pearson. “Each center has the opportunity to do pilot work, and they’ll be talking to each other to identify synergies across the centers.”

In line with NIMH’s commitment to addressing mental health disparities, the centers are focused on suicide prevention among groups and populations that are known to have higher suicide risk or are experiencing rapidly increasing suicide rates, especially those that face inequities in access to mental health services.

Addressing mental health disparities is also a pressing concern for Horowitz and colleagues as they continue their work with the ASQ.

“Right now, we’re focused on implementation and health equity,” said Horowitz. “It’s important to understand whether and how screening tools work for different populations that are known to have higher suicide risk.

American Indian/Alaska Native communities are one such priority population. Building on earlier pilot work, Horowitz and colleagues are collaborating with the Indian Health Service (IHS) to roll out suicide risk screening in IHS medical settings, including 22 emergency departments, around the United States.

Working directly with providers and administrators in different health care settings allows researchers to understand how contextual factors and structural constraints affect implementation.

“We’ve learned from researchers working in emergency departments, for example, that it’s difficult to bill for intervention components like safety planning and follow-up phone calls,” said Pearson. “That can pose a real problem when the interventions are key ingredients that help reduce people’s risk.”

This kind of work also underscores that successful implementation isn’t a one-time thing, but a continuous effort that is reinforced over time. For example, an extension of the ED-SAFE study suggests that quality improvement processes that promote ongoing training and monitoring can help sustain the effects of suicide prevention efforts.

Bending the curve

Soon after assuming the helm as NIMH Director in 2016, Dr. Gordon wrote about his commitment to suicide prevention as one of the institute’s top research priorities. He noted that building on promising findings from ED-SAFE and other NIMH-supported studies would give us “a chance to bend the curve on suicide rates, to save the lives of thousands of individuals.”

No one knew then that the coronavirus pandemic would upend life around the world just 3 years later, changing the landscape of mental health and mental health care in the process. Although it will take time to unpack the nuances of the pandemic’s long-term impacts, data point to wide-ranging effects on people’s mental health, including increased suicide risk for some.

“This is why research on suicide prevention in real-world settings is more important than ever,” said Pearson. “We’ve learned a lot since 2016, and a lot of the implementation work is just beginning. We hope this research will speed the translation of science into practice to help save lives.”