The Polluter Just Got a Million-Dollar Fine. That Won’t Cure This Woman’s Rare Cancer.

Rhonda Fratzke Credit:Joseph Ross, special to ProPublica

by Lisa Song

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

Series:

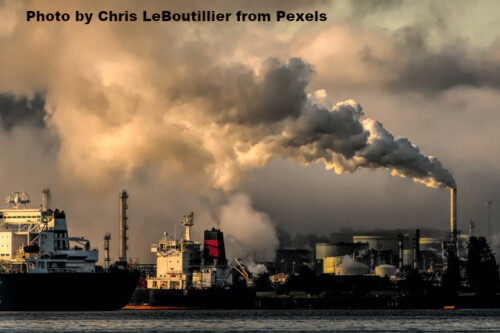

Sacrifice Zones

Mapping Cancer-Causing Industrial Air Pollution

Rhonda Fratzke recalls getting a strange question from her oncologist last year after she was diagnosed with cancer of the blood vessel linings: Had she ever worked with vinyl chloride?

Industrial workers exposed to the potent carcinogen, a colorless gas used to make plastic, have been known to develop the extremely rare ailment called angiosarcoma of the liver.

Fratzke, 60, spent much of her life as a homemaker. But for almost a decade, she lived near a plant in Calvert City, Kentucky, that manufactured polyvinyl chloride, a plastic known as PVC. ProPublica featured the Westlake Chemical Corporation facility in an investigation last month that revealed how regulators had failed to curb dangerous emissions, including vinyl chloride, from the company’s Calvert City operations. The cumulative cancer risk from vinyl chloride and other air pollution in the community surrounding Westlake’s plant far exceeded what the EPA considers acceptable, according to a ProPublica analysis and an EPA estimate.

Just three weeks after the story published, the Department of Justice announced a proposed consent decree that would require Westlake to pay a $1 million penalty and spend another $110 million to upgrade equipment at its Calvert City plant and at two of its other facilities in Lake Charles, Louisiana. The consent decree is a settlement between the federal government and the company that includes agreed-upon remedies for reducing Westlake’s environmental pollution and allows the parties to avoid going to trial. It targets Westlake’s industrial flares — giant candle-like devices that burn off waste gases. They’re supposed to destroy 95% of the contaminants piped into them, but Westlake repeatedly failed to operate them properly, according to the complaint, which was filed on behalf of the EPA and state environmental regulators in Kentucky and Louisiana. At times, the flares ceased working altogether, allowing all of the toxic waste to escape into the air.

The consent decree said Westlake denies violating any of the regulatory requirements that the EPA and state authorities said it had run afoul of. The company didn’t return requests for comment. In a statement provided to Law360, Westlake said it was “pleased to have reached an agreement with the United States Environmental Protection Agency and is making investments to reduce environmental emissions in concert with the company’s sustainability strategy.”

The news gave Fratzke a sense of validation. She and her family moved to Calvert City, near the Illinois border in Western Kentucky, in 1989. The following year, Westlake took over a local chemical plant, eventually expanding into three interconnected facilities. From 1990 to 1998 — which covers most of of the time Fratzke was living in the area — Westlake’s operations released 10,000 to 70,000 pounds of vinyl chloride per year, according to self-reported estimates that the company submitted to the EPA. That placed the company’s Calvert City plants among the nation’s top 10 industrial emitters of vinyl chloride for two of those years.

Those numbers are “absolutely astonishing,” said Arthur Frank, a Drexel University professor of public health and medicine. ProPublica shared details of Westlake’s history and Fratzke’s illness with the professor. “There’s a very high likelihood” that the vinyl chloride in the air “played a role,” he said.

In recent years, vinyl chloride emissions from Westlake have risen as high as 170,000 pounds a year, dwarfing emissions from other facilities in the city of 2,500.

It’s virtually impossible to prove that a specific contaminant caused any individual’s cancer. But Fratzke can’t help recalling how she raised four kids in that Calvert City house and spent countless hours growing roses and tomatoes in her garden. Was she breathing in extra vinyl chloride by spending all that time outside? Did the watermelon and squash she tended so carefully absorb the chemical from the soil? “Now I think, ‘Oh my God, what was I feeding my kids?’” Fratzke said.

Her youngest son, Jeremiah, rode his bike so much that he wore out the tires. She wondered: When he pedaled through the swampy area by the side of the road, was that water contaminated? Fratzke said Jeremiah was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma at age 23 and is now in remission. Exposure to certain chemicals — including benzene, which is emitted by the Westlake plant — has been linked to that type of cancer.

Westlake’s facility has a habit of leaking vinyl chloride; in 2011, for instance, 11,000 pounds of the compound streamed from a hole in a piece of piping that hadn’t been inspected. State and federal regulators have fined the plant for at least six instances of unauthorized vinyl chloride emissions since 2010, including twice since the EPA began investigating Westlake’s flares in 2014. A recent Kentucky air monitoring study also found high levels of vinyl chloride in Calvert City. From October 2020 to March 2021, two monitors installed near the Westlake plant recorded higher levels of vinyl chloride on average than any of the 129 other monitors nationwide designed to detect the chemical. A third monitor, on the grounds of Calvert City Elementary School, recorded levels in the top 10, according to data pulled from an EPA database.

It’s “ridiculous” how long it takes to investigate a violation, negotiate a consent decree and get the Justice Department to release it, said Scott Throwe, a former senior staffer in the EPA’s Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance. “It’s a very slow process” — around eight years, in this case — and “in the meantime the facilities are still chugging along and operating poorly, and the public is the one that suffers.”

Fratzke said she hopes the renewed attention on Westlake will raise awareness of local health risks. “They should notify the public” that they’re “in danger living this close to the plant,” she said.

She worried about other residents who might have angiosarcoma without knowing it. Fratzke only received her diagnosis after her doctor ordered extra tests to determine the cause of abnormalities found on her liver.

ProPublica asked the Kentucky Cancer Registry for data on statewide angiosarcoma cases. Based on national statistics and Kentucky’s population, one would expect four or five new cases a year. The most recent data available, from 2019, reveals 17 cases. The prior nine years saw eight to 18 diagnoses per year. Frank said the numbers do seem unusual, but it’s impossible to be sure if they’re linked to air pollution without having more information on the type of angiosarcoma and knowing whether the cases are clustered near industrial plants.

The settlement would require Westlake to reduce the amount of pollutants sent to the flares and to ensure that the flares are working as they should. These changes would cut the plants’ hazardous air pollution by 65 tons per year and reduce its volatile organic compounds (which form smog) by 2,258 tons per year, the regulators predicted. Westlake will also install monitors around the boundary of each facility to monitor for benzene, a potent carcinogen.

Throwe said the document is powerful, with “a lot of teeth.” But it will only work if the EPA monitors Westlake to ensure the requirements are being implemented, he said. Without follow-up, “it’s not worth the paper that it’s written on.”

The EPA’s Washington, D.C., office, which led the investigation into Westlake that resulted in the consent decree, did not respond to requests for comment.

After a public comment period (which ends July 15), the agreement will be finalized if it receives court approval. (Instructions for submitting comments can be found here.) Throwe said consent decrees rarely receive many comments, and he doesn’t expect the terms of the final agreement to change much, if at all.

Few leaders in Calvert City were willing to criticize Westlake, ProPublica found during a reporting trip this spring. In surrounding Marshall County, more than a quarter of the private-sector jobs come from chemical plants and other manufacturing.

“What is particularly sad about this situation is, this is a small company town,” Throwe said. Westlake is “significantly impacting the health of their own employees … and the children that live in the community.”

Fratzke now lives 9 miles outside Calvert City. In the winter, when the leaves are off the trees, she can see the glow from Westlake’s flares. “It just lights up the sky,” she said.

“I’m not putting down Calvert City, I’m not putting down the plant,” she said. Westlake pays taxes and donates to the community, including the high school where her grandson enjoys more resources than what’s available at other schools, she said. The companies “pay and do all that stuff, I think, to keep people happy. … So I think people tend to turn their head the other way as the money flows.”